|

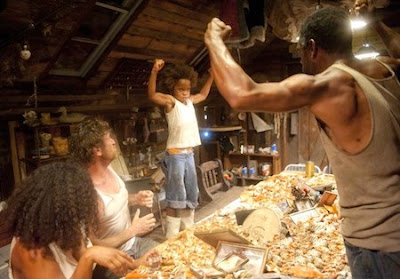

| Photo from Fandango.com |

As I watched Benh Zeitlin’s poetic, gorgeously filmed movie, I kept asking myself: who are these Beasts of The Southern Wild? Of course, they are prehistoric Aurochs, encased in Ice Age glaciers, set free by the same storm that threatens Hushpuppy’s (Quenzhané Wallis) home. But, as a psychoanalyst, I can’t help but reflect on the mythical Beasts in Hushpuppy’s mind. After all, they appear and re–appear, at crucial points in the film, when storms of feeling threaten to overwhelm a little girl who, in spite of her resilience, is quite alone. There is a mother who ‘swam away’, an erratically loving, angry, and dying father (Dwight Henry) - teaching Hushpuppy to be “The Man”, fiercely tough and, especially, never, never sad.

When a mother leaves, and a father is dying, a child too frequently blames herself. Her need, her anger, her hurt – those (misinterpreted to be beastly) feelings - must have done it. She constructs a tough wall against her feelings and love’s unreliability; like when Hushpuppy lashes out at her dad: “I hope you die and when you do, I’ll go to your grave and eat birthday cake all by myself” - as if she doesn’t care. When he disappears from the place he has suddenly fallen, she’s terrified: “I’ve broken everything”. Did her angry wishes turn him into a tree, or maybe a bug? Will he ever come back?

“The whole universe depends on things fitting together just right. If one piece falls apart, the entire universe would get busted”. Hushpuppy’s world is falling apart; an internal voice, in voice over, is trying to sort out her fear that she’s the one who’s done the busting. That’s hard, though, with no help. When the film pans to an Ice Age scene with the world frozen over, we know Hushpuppy’s trying to toughen up; to be “The Man”.

Toughness is her dad’s way, too, and keeping those Beasts (of feelings) encased in ice is what he wants. If there is any tender kind of “girl stuff”, he aggressively yells: “Beast it, Hushpuppy…. Beast it, Beast it, Beast it.” A litany. A chorus; until Hushpuppy is showing her muscle-guns: “No time to sit around crying like a bunch of pussies”. Feelings of sadness, love, and need won’t be quieted, though, and the Beasts burst through at every turn - with Hurricane Katrina, a backdrop for the storms of a little girl’s troubling emotions.

“Sometimes you can break something so bad you can’t get it put back together again.” Hushpuppy’s fear: that she’s “eaten her own Mommy and Daddy” - as all children do, in their understandably greedy need for love and security, to stave off the fear of loss. Hushpuppy, too adult, tries to face what she must: “Everyone loses the thing that made them. The brave must stay and watch it happen. They don’t run”.

This little brave one finds her Mama and brings back Mama-cooked fried alligator; a last- meal love offering for her dad. The Beasts chase her, close behind. These Beasts are her Beasts - feelings of sadness, loss, and fear that must be felt. As Hushpuppy fiercely turns to face them, one of the Beasts kneels before her. Softening, she says: “You’re my friend, kind of”; not sure how safe her feelings are quite yet. As her dad holds her and they finally share a tearful goodbye, Hushpuppy’s Ice Age wall of toughness begins to melt: “When it all goes quiet behind my eyes, I see everything that made me . . . all the pieces are there”. Yet, that wall, like the levee, needs time to deconstruct. There is still a lot of mourning to do.